The Tree and the Web: Why Darwin and Kumagusu Drew Different Maps of Life

The Geometry of Time vs. The Geometry of Space

(Author’s Note: Two geniuses in the 19th century tried to sketch the “shape of life.” One drew a tree; the other drew a web. Why? The answer lies not just in their brains, but in the geography they stood upon and the deep personal dramas they lived.)

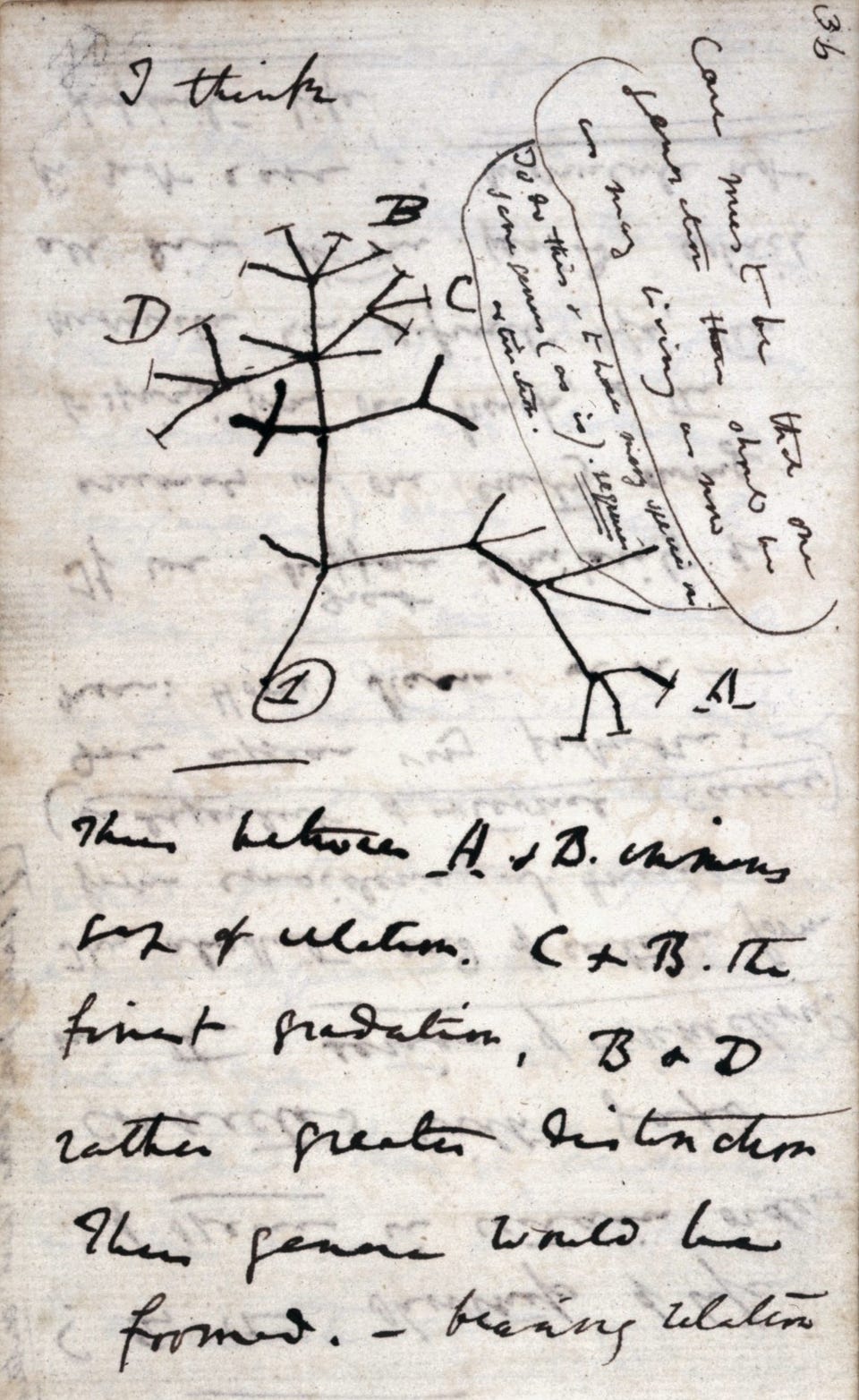

Look at this sketch. A few simple lines branching out, with the words “I think” scrawled above them.

This is the moment Charles Darwin visualized the history of life as a “Tree”—a symbol of time, divergence, and evolution.

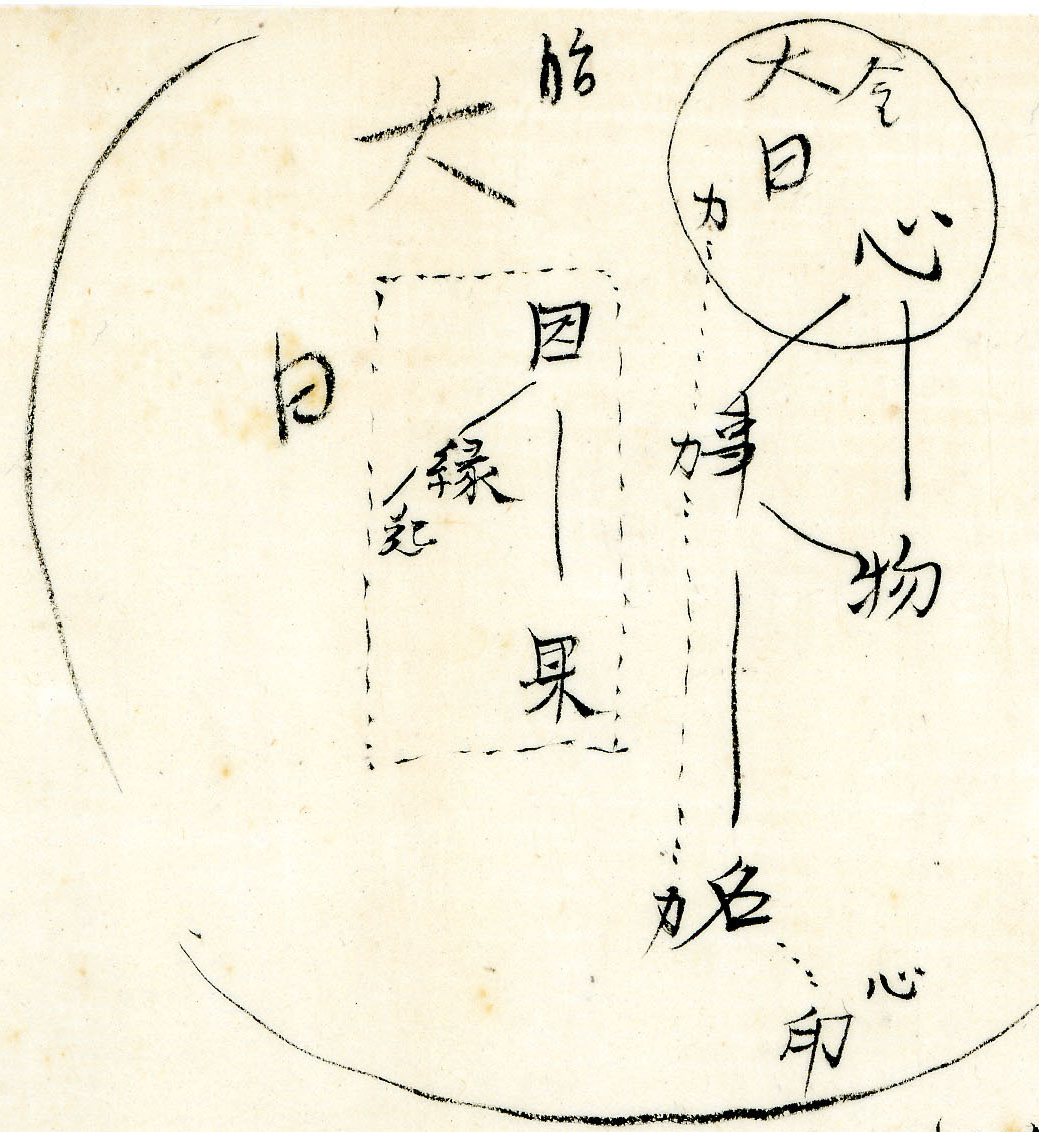

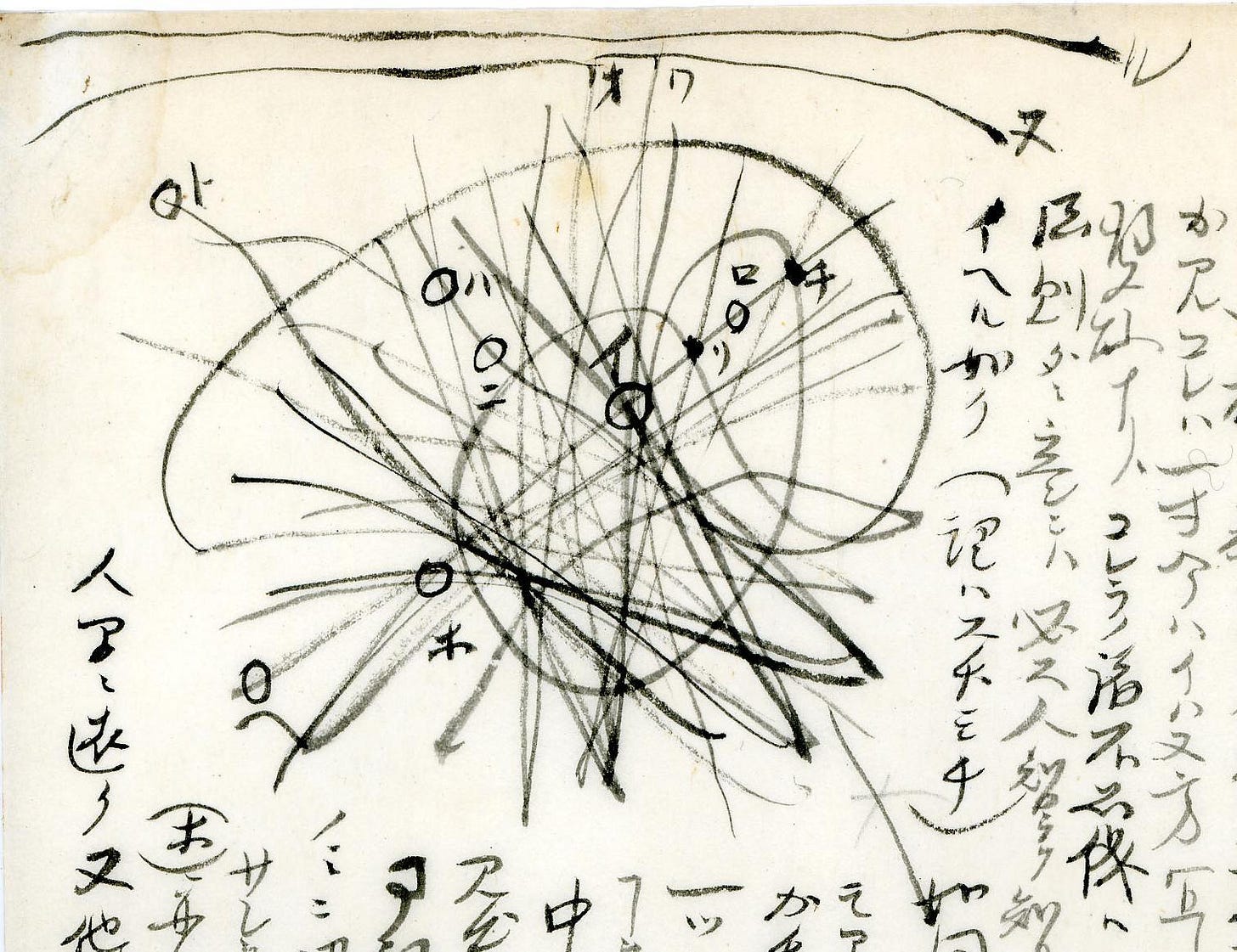

Now, look at this diagram. Countless lines crisscrossing, circles overlapping with no beginning and no end. This is the “Minakata Mandala” drawn by the Japanese polymath Minakata Kumagusu.

It depicts a world where multiple realms—Matter, Mind, Language, Spirit, and the Divine—overlap without boundaries. Kumagusu called these the “Five Mysteries.” It is a symbol of “Space”—a web where cause and effect are woven together in the present moment.

Both men were giants of the 19th century who sought to capture the essence of life. Yet, one saw a vertical hierarchy, while the other saw a horizontal network.

Why?

If we play detective and examine the “places” where they stood and the “pain” they carried, a striking contrast emerges.

Clue 1: The Solitary Island vs. The Dense Forest

Why did Darwin see a “Tree” while Kumagusu saw a “Web”? The first clue lies in the geography that shaped their thinking.

Darwin’s Laboratory: The “Isolation” of the Galapagos

Darwin’s epiphany came from the Galapagos Islands. Look at the map of this archipelago. It is a collection of isolated fragments scattered in the vast Pacific.

Here, Darwin noticed that finches on different islands had evolved different beaks. The key factor was “Isolation.”

Because the islands were separated by the sea, life could not mix. It diverged. In this geographical condition, the history of life inevitably looks like a “family tree” that branches out from a common ancestor and never meets again.

To explain this, Darwin needed a “Vertical Axis” (Time). His “Tree of Life” is a diagram of Time—showing how order and divergence are created over millions of years.

Kumagusu’s Laboratory: The “Density” of the Kii Forest

On the other hand, where did Kumagusu stand? After 14 years of wandering the world (USA, Cuba, London), he didn’t stay in the “center of civilization.” He returned to the forests of the Kii Peninsula (Kumano/Nachi) in Japan.

This is not a dry, isolated island. It is a warm, humid, and incredibly dense temperate rainforest. Here, plants, mosses, insects, and bacteria are densely packed, rotting, and regenerating in a chaotic cycle.

In this environment, “isolation” does not exist. Everything is connected. The boundaries between life and death, self and other, blur into a single “Gradient.”

For Kumagusu, this forest was Japanese culture itself. He didn’t see folklore, religion, and nature as separate things.

“Mountain Worship” was the reverence for the terrain itself.

“Chinju-no-Mori” (Sacred Forests) were the community centers.

“Foxfire” (Ghost lights) were not merely supernatural tales; he analyzed them as chemical reactions of combustible gases determined by the wetland geography and forest composition.

To explain this, Kumagusu needed a “Horizontal Axis” (Space). His “Mandala” is a diagram of Space—showing how the environment, ecology, and human spirit are knotted together in a single mesh.

Clue 2: The Silence of Love vs. The Scream of Anger

But geography wasn’t the only factor. The societies they lived in—and the people they encountered—deeply carved the maps they drew.

Darwin’s Silence: Emma and the 20-Year Delay

Darwin drew his “Tree” sketch in 1837, but he didn’t publish The Origin of Species until 1859. Why did he wait over 20 years?

It wasn’t just scientific caution. It was Love. His wife, Emma, was a devout Christian.

When Darwin hinted at his theory that “species are not immutable creations of God,” she was terrified. She wrote him a letter sharing her deepest fear: that his heresy would separate them in the afterlife—“I will go to heaven, and you will go to hell.” Darwin wasn’t a cold logic machine. He kept this letter all his life, writing on it: “When I am dead, know that many times I have kissed and cried over this.”

He lived in Victorian England, a society shifting from tradition to industrialization. To publish his theory meant destroying the world his beloved wife believed in. To bridge this gap, he retreated to the quiet countryside of Down House. He needed his theory to be an “Unshakable Fortress.”

So, he spent eight long years dissecting Barnacles. Barnacles are creatures of “fixed identity” protected by hard shells. By classifying them obsessively, Darwin sought to build a pile of irrefutable evidence that could withstand the storms of society.

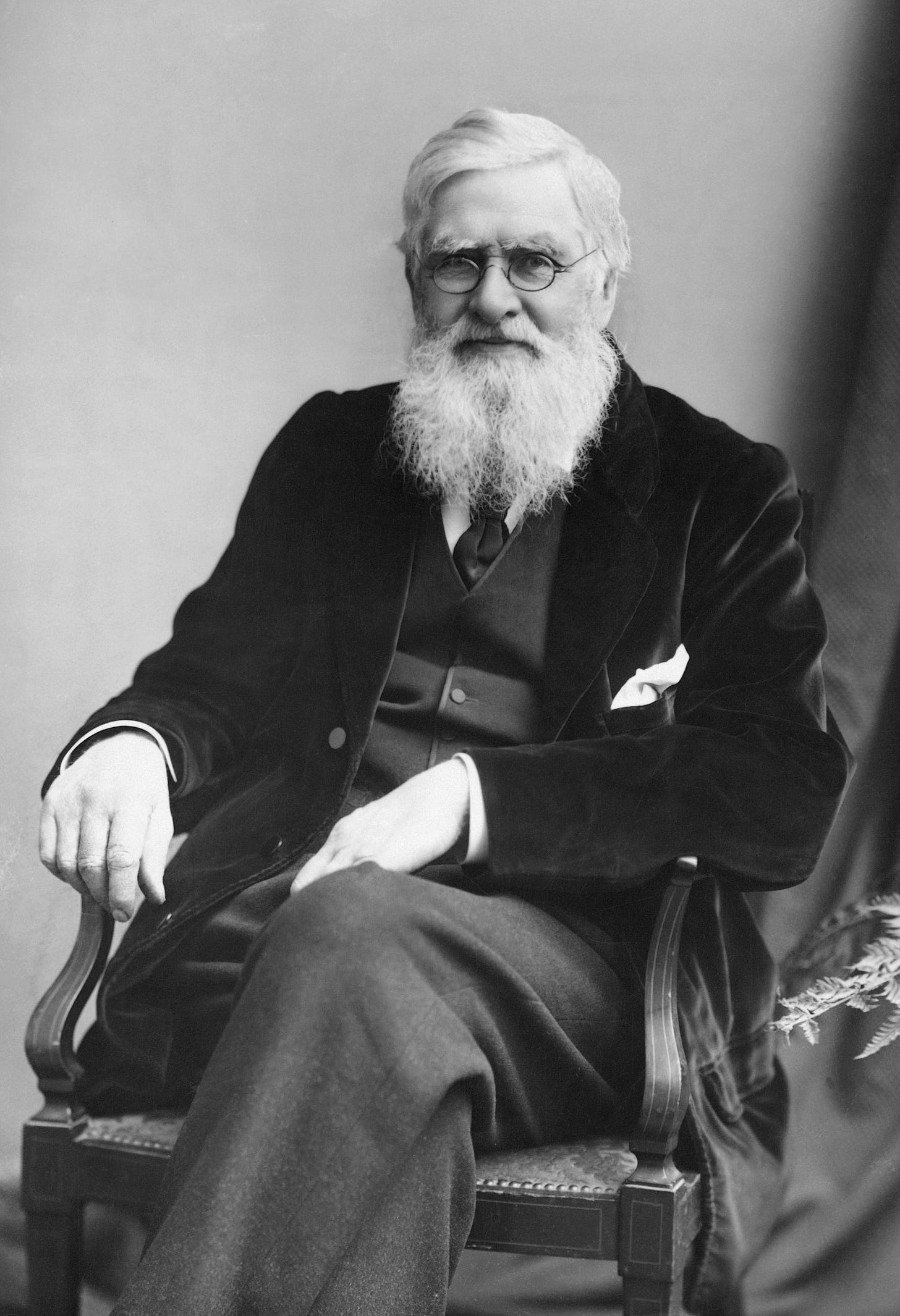

The Trigger: A Letter from Russell (Wallace)

But the fortress could not stay closed forever. In 1858, a letter arrived from a young naturalist working in the Malay Archipelago: Alfred Russel Wallace.

The letter contained an essay detailing a theory almost identical to Darwin’s natural selection. Shocked by this “bolt from the blue,” Darwin realized he could no longer remain silent. With the help of his friends Lyell and Hooker, he arranged a joint presentation, forcing the birth of The Origin of Species.

Kumagusu’s Anger: The Rebel in the Empire

Kumagusu, on the other hand, had no fortress and no wife to protect. In London, the heart of the British Empire, he was a paradox. He was a brilliant scholar who contributed frequently to the journal Nature, yet he lived in abject poverty.

At the British Museum, he faced the cold reality of the Empire: discrimination. Despite his vast knowledge, he was treated as an outsider. This tension exploded in a violent altercation with museum staff, leading to his expulsion. He turned his back on the “Order of the Empire” and looked at the ground.

He became obsessed with Slime Molds (Myxomycetes). He collected them not just in Japan, but in the US and Cuba, even discovering a new genus later named Minakatella longifila.

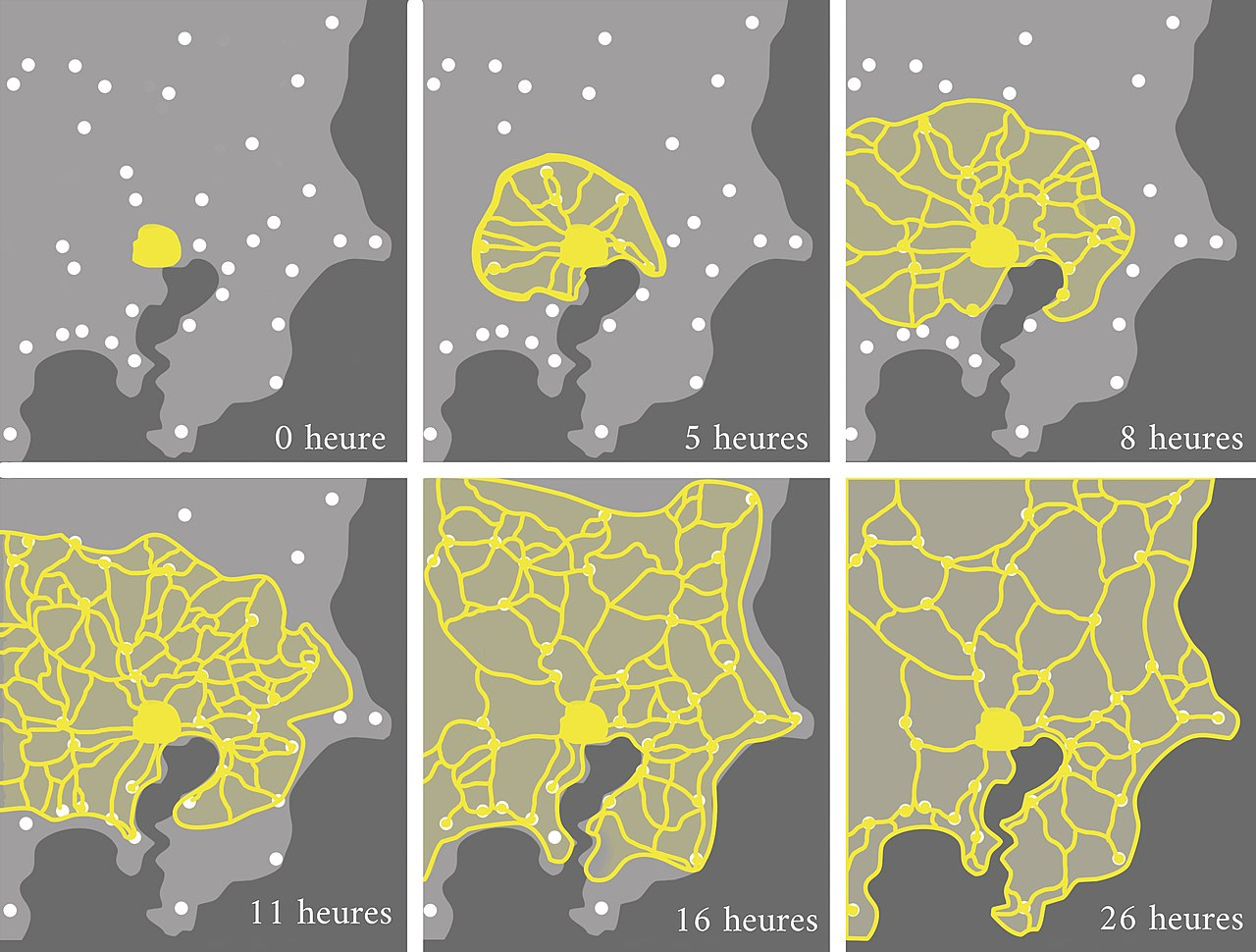

Look at this creature. It is neither animal nor plant nor fungus. It defies traditional classification. It moves, eats, and transforms. It has no central brain, yet it survives.

For Kumagusu, this “Decentralized Fluidity” was the truth. Interestingly, modern science has proven him right. In the 21st century, experiments with the slime mold Physarum polycephalum showed something shocking: when placed on a map of the Tokyo area with oat flakes representing cities, the slime mold self-organized into a network almost identical to the actual efficient railway system designed by human engineers.

“Slime Mold Computing” proved that intelligence doesn’t require a central command (a brain). While Darwin sought a centralized “System” to survive society, Kumagusu sought a decentralized “Network” to understand the chaos of nature.

Clue 3: The Battle for the Future — “Development” vs. “Ecology”

These two worldviews—the Tree and the Web—eventually led to two very different conclusions about how humans should treat nature.

The Shadow of the Tree: “Competition”

Darwin’s theory of “Survival of the Fittest” was revolutionary, but it had a dangerous side effect. Society interpreted it as a justification for “Competition.”

If life is a struggle where the strong survive, then capitalism, imperialism, and the exploitation of nature can be rationalized. The “Tree” became a ladder for humans to climb, conquering nature along the way.

The Cry of the Web: “Coexistence”

Kumagusu fought against this. In the early 20th century, the Japanese government pushed for “Shrine Mergers”—a policy to destroy small village shrines and merge them into larger ones to “rationalize” religion. This meant cutting down the “Chinju-no-Mori” (Sacred Forests) protecting those local shrines.

Kumagusu waged a fierce one-man war against this policy. He argued that destroying a small patch of forest wasn’t just about losing trees; it meant tearing a hole in the “Web.” Loss of the forest meant loss of shade, which meant loss of moss and slime molds, which meant loss of insects, which eventually destroys the local ecosystem and the human culture rooted there. He intuitively understood what we now call “Ecological Resilience.”

He realized that “cutting one thread unravels the whole cloth.” This was one of the world’s earliest ecological movements.

Conclusion: The Caramel Box and the Emperor

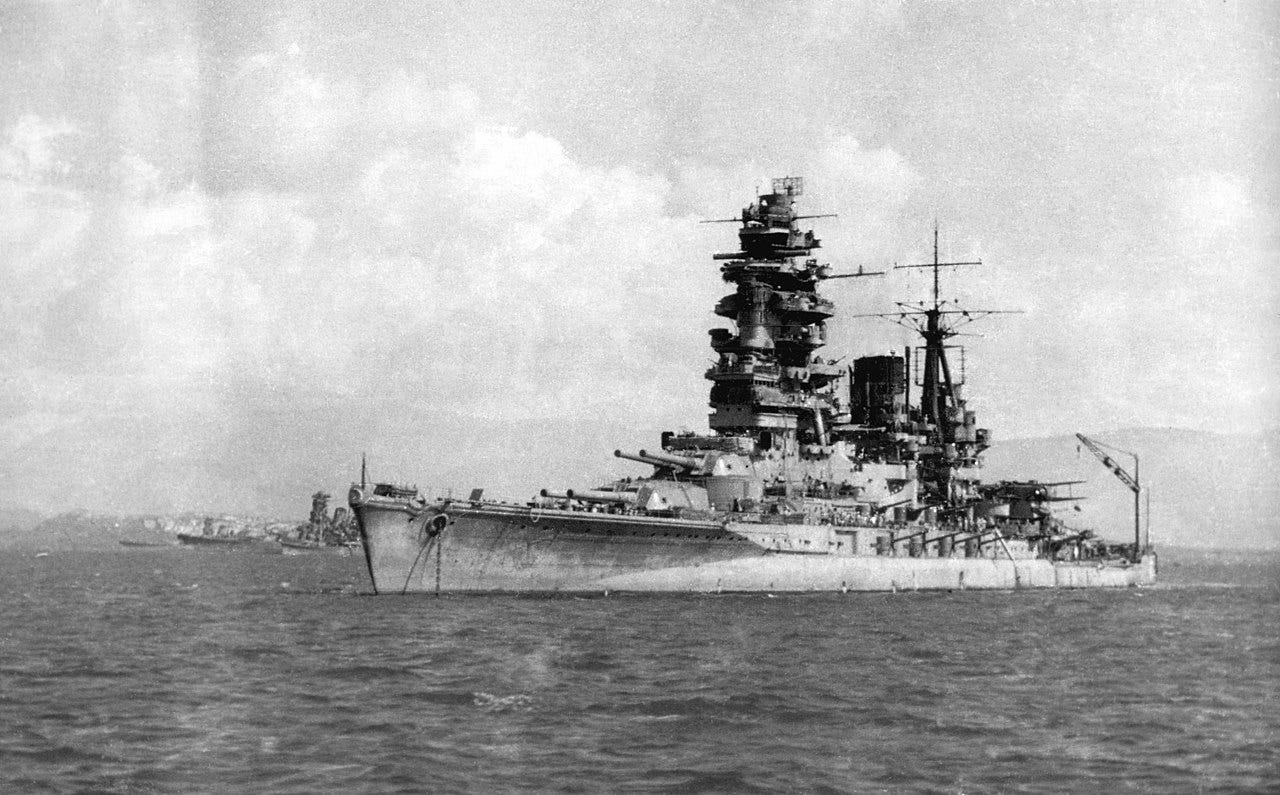

In 1929, an extraordinary meeting took place. The Showa Emperor (a biologist himself) visited the Kii Peninsula, and Kumagusu was invited to give a lecture on board the battleship Nagato.

Kumagusu, known for his eccentricity and dirty clothes, dressed in a frock coat and brought his precious specimens. But he didn’t put them in expensive wooden boxes. He presented his slime molds to the Emperor in empty caramel boxes.

Why caramel boxes? Perhaps he wanted to show that the “truth of the universe” doesn’t need decoration. It exists in the humblest, stickiest, most overlooked corners of the forest. The Emperor later wrote a poem remembering him: “Seeing the rain on Kashima, I think of Minakata Kumagusu, born of the land of Kii.”

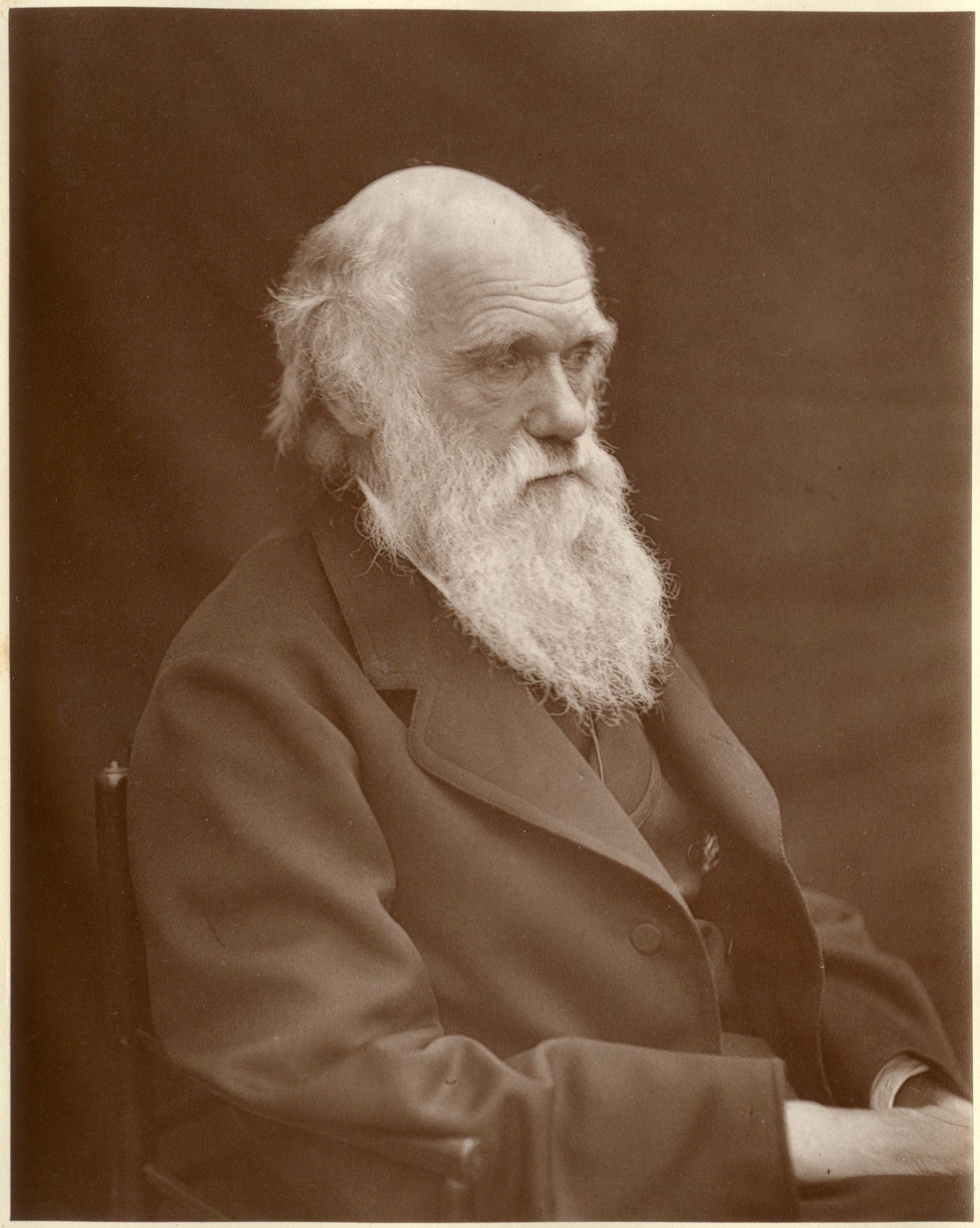

The end of their lives also reflected their maps. Darwin was buried in Westminster Abbey, honored as the father of modern biology—a pillar of the establishment. Kumagusu died in his humble home. On his deathbed, he whispered, “Purple flowers are blooming on the ceiling... if the doctor comes, they will disappear, so do not call him.” He passed away watching the “flowers” of the Sendan tree (or perhaps a vision of his Mandala) vanish.

We need both maps. We need Darwin’s “Tree”—the vertical logic of science, time, and evolution. But today, as we face climate change and biodiversity loss, we desperately need Kumagusu’s “Web”—the horizontal wisdom of connection, empathy, and ecology.

The “Order” of the dry land and the “Chaos” of the deep forest. Only by overlapping these two maps can we navigate the complex territory of the 21st century.

Researcher’s Toolkit

Data sources referenced in writing this article. A list of primary information and recommended materials for those who want to dig deeper.

1. Understanding Minakata Kumagusu’s Thought

Minakata Kumagusu Archives (Tanabe City): Link

Commentary: An archive located next to Kumagusu’s former residence. It houses his massive collection of books and materials, and provides detailed articles on the “Minakata Mandala.” The “Life of Kumagusu” and “Research Achievements” pages are a treasure trove of basic knowledge.

Minakata Kumagusu Museum (Shirahama): Link

Commentary: Located in Shirahama. You can view materials such as photos of the lecture to the Showa Emperor, slime mold specimens, and his death mask.

2. Tracing Darwin’s Voyage

The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online: Link

Commentary: The world’s largest Darwin archive, run by Cambridge University. You can view his handwritten notebooks (including the “I think” sketch), all editions of The Origin of Species, and the Beagle voyage records for free.

3. Modern Science and Slime Molds

Ig Nobel Prize Research: Slime Mold Railway Networks: Link

Commentary: The research by Professor Toshiyuki Nakagaki (Hokkaido University) mentioned in the article is widely introduced on science news sites. Searching for “Slime mold railway network” will show you actual experiment images of slime molds spreading over maps of the Tokyo area.

4. Recommended Books (Further Reading)

“The Origin of Species” (Charles Darwin / Translated by Masataka Watanabe)

Commentary: Darwin’s writing is actually very cautious and full of consideration. Reading it reveals how carefully he chose his words to build his “fortress of stone.” Chapters 3 (Struggle for Existence) and 4 (Natural Selection) are must-reads.

“Minakata Kumagusu: The Dream of Omniscience” (Ryugo Matsui / Minakata Kumagusu: Issai-Chie no Yume)

Commentary: The definitive biography by a leading Kumagusu scholar. It dramatically yet accurately depicts his days in London, his activities in the Nachi forest, and the ideological background of the “Minakata Mandala.” Recommended for those who want to peek inside the head of the “walking encyclopedia.”

“Earth-Oriented Comparative Studies” (Kazuko Tsurumi / Minakata Kumagusu: Chikyu Shiko no Hikaku-gaku)

Commentary: A masterpiece by a sociologist who structured Kumagusu’s thought using the “Minakata Mandala” model. It deeply considers the “Suiten” (intersection point) and the fusion of science and Buddhism. Highly recommended for those who want to grasp the world as a system.

“The Voyage of the Beagle” (Charles Darwin / Translated by Hiroshi Aramata)

Commentary: An adventure story and a first-class travelogue by the young Darwin. You can relive his gaze as he observed the wilderness of Patagonia, fossils in the Andes, and creatures of the Galapagos.

“Slime Molds: Their Amazing Intelligence” (Toshiyuki Nakagaki / Nankin: Sono Odorokubeki Chisei)

Commentary: A book by the leading expert on “networks created by brainless organisms,” the theme of Chapter 3. Through stories of maze-solving slime molds and urban planning slime molds, you can learn about the possibilities of “decentralized networks.”

Join the Search for "Survival Strategies"

Geography is not about memorizing maps; it is a record of survival strategies. Through this newsletter, I analyze the “World-Building” of our planet—from the volcanoes of Indonesia to the streets of New York—to uncover the hidden logic of history and geopolitics.

Support Independent Research By becoming a Paid Subscriber or Founding Member, you are directly funding the field research and analysis needed to decode these global complexities. Join us in increasing the resolution of how we see the world.